[Below is a review of Carolyn Osiek’s book Beyond Anger: On Being a Feminist in the Church that I wrote for a David Scholer's class "Women, the Bible, and the Church" I am taking in my final quarter at Fuller. Whoohoo!]

Carolyn Osiek’s book Beyond Anger: On Being a Feminist in the Church, is a powerful message of concern and courage to women who are called to positions of leadership within the church. Osiek draws from personal experience and other women’s stories to give an account of women dealing with the anger and frustration of the church’s gender-bias and patriarchal oppression. According to Osiek, women “sell ourselves short in order not to offend” [10], especially in relation to the powerful Christian symbol of the cross. Osiek explains:

Carolyn Osiek’s book Beyond Anger: On Being a Feminist in the Church, is a powerful message of concern and courage to women who are called to positions of leadership within the church. Osiek draws from personal experience and other women’s stories to give an account of women dealing with the anger and frustration of the church’s gender-bias and patriarchal oppression. According to Osiek, women “sell ourselves short in order not to offend” [10], especially in relation to the powerful Christian symbol of the cross. Osiek explains:

"Women are to imitate the victim Christ while at the same time they are denied any possibility of fully identifying with him. Doomed to be like him in suffering and humiliation, they are equally doomed to be unlike him in power, authority, or exaltation." [10]

Osiek continues in the first chapter to encourage women that they need not give up their faith because of its abuse by those in power. She uses the language of fear, danger, and enslavement and asks women to move into language of courage, light, and liberation. Instead of being devastated by a self-perception of “the myth of male superiority” [10], women can recognize their repression and realize the emptiness of the myth. The newfound awareness and realization of the reality of a male dominated society leads women to anger, which Osiek believes is a “useful emotion” [13]. But women may choose not to appropriately express that it, and the built-up repressed anger can lead to depression and sadness with the angry women being “forced to find her support predominantly among other angry women” [14]. Although “anger is a completely appropriate response to the awareness of oppression” [16], Osiek warns that “depression, emptiness and joylessness are symptomatic of the experience of impasse” [23] which she believes is not a final resting place for the anger.

In the second chapter, Osiek explains different definitions of possible “feminism” and considers the different ways she perceives women as coping. The “marginalist” remains an angry person “whose anger festers and goes only in destructive directions because her energies have no creative outlet” [28]. The “loyalist” raises questions from within the church, but does so “quietly and loyally” [30]. The “symbolist” concentrates her attention on the feminine characteristics of God, but is in danger of advocating superiority of the feminine over the masculine. The “revisionist” believes that “the patriarchal cast of the Judeo-Christian tradition is due more to historical and cultural causes than theological ones” [38]. Finally the “liberationist” is defined as one who believes in the conversion of society, but picks and chooses Biblical text that is relevant to the society in which we live. Osiek does not present one coping response or method above another, but believes that women have “the responsibility to consciously choose our ways of dealing with the consequences. To let them be chosen for us is to fail to assume responsibility for our own destiny” [43].

The third chapter of the book explains that an “impasse” is reached by each of these coping responses or methods. In order to breakthrough the impasse, women must move towards a “conversion” that discovers of new perspective where the “previously acceptable is so no longer” [45]. Osiek explains the individual spiritual conversion that each woman must accept, and also outlines the institutional conversion of the church that must take place. The institutional conversion hopes for a future where power can be “gradually and willingly shared” [57-58]. Both conversions are interrelated in that “just as there is no structural conversion without personal conversion, so there is no structural transformation without personal transformation” [61]. I believe this is where Osiek is prophetic in her alliteration of the feminist struggle. For true transformation of the institution must come from individual transformation, a transformation from within the institution. This transformation does not come without a price. “There is a price to be paid for human growth – soul-searching honesty required to follow through on insight” [63], Osiek explains. Power and gender roles must be “recovered, reclaimed, and reappropriated into a new context where it will no longer aide the cause of oppression and passivity” [65].

Osiek’s last chapter reflects on the paradox and “contradiction” of the “cross” [74]. Osiek explains that through the pain of the cross comes life. And furthermore, that through the ability to “freely surrender” [79] comes a true sense of self and liberation. The message is not to lie down and take it:

"It is not forgive and forget, as if nothing wrong had ever happened, but forgive and go forward, building on the mistakes of the past and the energy generated by reconciliation to create a new future." [76]

This is a message of hope springing from the repressed anger of injustice and oppression. Osiek believes there is “no transformation of a person or society without suffering” and that “only the suffering will devote themselves to alleviating suffering” [83]. This is where the power struggle comes full circle towards a message of empowerment through the anger and suffering subjected by an oppressive patriarchal society. Through the experience of pain comes an awareness that “leaves ignorance behind and arrives at the illuminating knowledge of full feminist consciousness” [84].

Osiek concludes with practical strategies to women who are in the struggle towards equality. She reiterates the exclamation that women must choose their own beliefs and strategies and not let “them to be chosen for you” [87]. Osiek appropriately ends with a reminder that, “the Church of the present and the future is counting on you” [87].

My initial response to the book is two-fold. It is clear that although Osiek was venting her frustrations of living out her calling in an oppressive patriarchal society, she did so by treading lightly around the subject of oppression and women’s suffrage. Dr. Scholer explained that Osiek has later admitted that, “We sell ourselves short in order not to offend.” And her lament that women must “have the strength to be weak” [87] demonstrates this tiptoeing around the subject in order not to condemn the oppressors of women: men. But an attack on the men that besiege women isn’t the goal of the book. Rather, Osiek presents a text designed to help women deal with the oppression of “male superiority” that the Church culture still presents.

My own views on women in leadership have been shaped by my family upbringing upholding the value of women as equal in every way, my studies as a seminarian at Fuller Theological Seminary and by my personal ministry in the Emerging Church movement for the past 6 years. Most of that time, I was single. And now in the past few years, I have been married to a supportive Christian layperson, a self-proclaimed feminist quite willing to take on any oppressor. As I studied the scriptures, my views strengthened the support of women in leadership that, in order to be true to the whole of scripture, I had to support the notion that women, who were so gifted and called by God should exercise responsible leadership in both society and the church. In addition, I am proud to say that I am part of the online Facebook group:

Real Men are Feminists.

If I had to chose which of Osiek’s outlined coping methods I fall into, I would definitely say that the “liberationist” view a “hermeneutic of suspicion” [41] best defines my viewpoint and role in the feminist movement. It is easy to focus on the anger and repression of the story Osiek details. But I naturally migrate towards the positive affirmation and encouragement Osiek reflects. Her statement that, “There is more than one way to read history, and that we have been traditionally locked into only one perspective: the patriarchal one” [38], is a wise reflection on the historical place of the oppression of women and has an underlying message of hope for the future. It is a brilliant tactic. The briefly mentioned reminder of the book is that, “the challenge and the goal is

reform” [38]. Unfortunately, I think Osiek’s concluding strategies of surviving and thriving in the culture are not a message of reform, but one of coping and dealing with the anger of a society that cannot change.

Even as a man reading about women struggling in a oppressive culture, the hope of “transformation of human society through conversion” [41] resonates within my soul. I am admittedly saddened by the stories of struggle towards equality in the Church that women are forced to deal with, while at the same time encouraged and fired up about the thought of women and men choosing a destiny of equality of a history of traditional patriarchal structures. Osiek’s belief that we can discover a “new perspective from which what was previously acceptable is so no longer” [45], is one that both men and women can hold. The price must be paid from both sexes to bury oppression in a final resting place of history, and to reclaim a present reality of true equality.

Tomorrow, we will elect the next President of the United States. The result will have great consequences for the nation. This election offers a choice between two men with dramatically different visions of the future. We have strong feelings about this choice. But we feel even more strongly that all Americans, regardless of political preference, have a stake in the outcome and should vote in this critical election.

Tomorrow, we will elect the next President of the United States. The result will have great consequences for the nation. This election offers a choice between two men with dramatically different visions of the future. We have strong feelings about this choice. But we feel even more strongly that all Americans, regardless of political preference, have a stake in the outcome and should vote in this critical election.

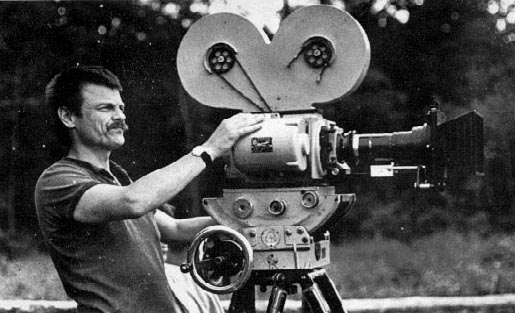

And the blame is in the direction. The movie is dated beyond-belief. From the 80's dress, to the 80's music... the 80's haven't aged well. You can see the glimpses towards the transcendental filmmakers that Schrader idolizes, but they are over-the-top in every way. From obviously placed buddhas on empty walls, to lonely cross-shaped lamps in empty rooms... the film wants to introduce divine grace in a troubled world, but doesn't have the touch of grace needed to pull it off. I love lamp. I hate Schrader's direction.

And the blame is in the direction. The movie is dated beyond-belief. From the 80's dress, to the 80's music... the 80's haven't aged well. You can see the glimpses towards the transcendental filmmakers that Schrader idolizes, but they are over-the-top in every way. From obviously placed buddhas on empty walls, to lonely cross-shaped lamps in empty rooms... the film wants to introduce divine grace in a troubled world, but doesn't have the touch of grace needed to pull it off. I love lamp. I hate Schrader's direction.